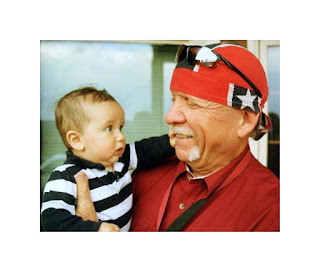

Immortalized in my memory as the transient

smell of sweat and leather, he (my father) exists as a sort of

paradox. I think of him as a giant in his pilot uniform; as a boy,

anywhere we went in the world people knew him. I heard strangers

excitedly call his name in myriad accents, in busy international

terminals and rural gas stations alike. However I am also keenly

aware of his many vexations, demons that hounded him mercilessly for

most of his life. In the end I envied him, laying emaciated in bed

and riddled with cancer, for his inability to supplicate them.

“Come to the window, sweet is the

night air!” penned Matthew Arnold sometime around 1850. One hundred

and forty-nine years later, this lyric from my favorite verse would

parallel my most cherished experiences with dad. After my parents

divorced, we were living in Fulton County, Pennsylvania with mom and

he in Manila, Philippines. From time to time he would appear, and

stay at his sisters sprawling log/ nursing home half an hour or so

away from our trailer, and I would go join for a few days at a time.

Inevitably sometime in the cool dead of night, after the dew had

begun forming outside on the hood of the car, he- jetlagged and

unable to sleep- would wake me up. I don't remember ever getting

dressed, just that at some point we would be driving east on Route

70.

There were never any passenger cars on

the road at that time save for ours, an older Buick dad would borrow

from my Aunt with a sort of black corduroy upholstery and square

chromed seatbelt buckles. We would drive in silence at first, as I

gradually woke up in the front seat, and he would begin talking. Not

like a teacher talks to a student, or like a mother talks, but like a

man talks to another man at a campfire as it fades into the night. He

would tell me great secret things, the preposterous and unimaginable

secrets of life, as if I already knew them and he was just

acknowledging the obvious.

I would listen wide-eyed. He told me

of girlfriends he had wooed before meeting my mom, he told me to “treat niggers and retards and poor people the same as I would treat

him”, he told me about the time he stole a chicken from a neighbors

farm and plucked it and cooked it over a fire in an orange grove, and

about the time he woke up in the cockpit and thought the full moon

was another airplane heading straight at him. Sometimes he would say

“shit” or “fucking”, and I would feel very grown up.

Eventually we would reach our

destination, which was almost always Little Sandys 24-hour truck-stop

in Hancock, Maryland. It is a greasy, crumb-covered, loathsome place,

but at the time seemed cooler at least than the finest Michelin dining. We

would park our sedan somewhere amongst the gargantuan idling semis,

where fat men snored or bargained with prostitutes in their sleeper

cabs, and walk in. Imagine how my chest swelled! Being born in the

south dad loved grits, a trait I failed to acquire despite his

repeated entreaties, so I would get an omelet. The grumpy, red-eyed

aproned matriarch would bring him coffee and me hot chocolate in

thick, heavy ceramic mugs with stain rings they had probably been

serving in since the seventies.

After eating and making sure I saw him leave a

few dollars tip, we would thank the lady and exit, pausing to sit on

a bench by the door outside. Dad would smoke a cigarette and flick

the butt what seemed to me like halfway across the parking lot, while

bemoaning the latest cruelty inflicted by his latest girlfriend

(undoubtedly in response to some unmentioned cruelty on his part) and we would

drive home in silence. I don't ever remember going back to sleep.

The last time I saw him, he was mostly

bedridden. His fourth wife, younger than I, was cleaning and feeding him

daily. On one occasion he opened his eyes, and began describing in

great detail an experience from decades earlier. He had been hired to

fly cargo on a south-westerly route, and as such experienced a much

longer than usual sunset from the altitude of 27,000 feet. As he told

of skimming along the tops of the red clouds, his gray eyes watered

and his lip quivered. “I never told anyone about that”, he said simply,

his voice cracking.

It must have been beautiful.